Explanation to the Theory:

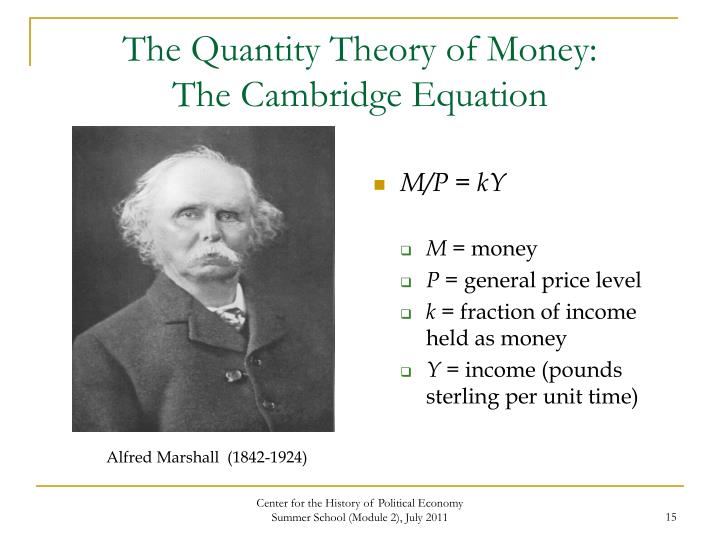

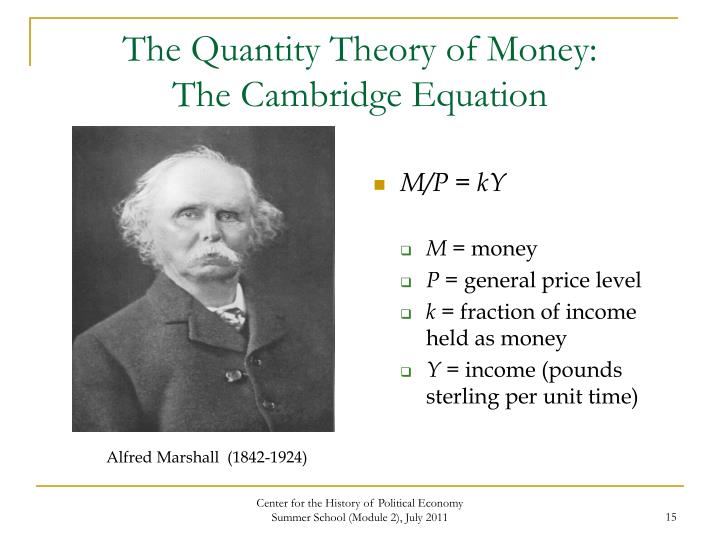

The Cambridge economists—like Alfred Marshall and A. C. Pigou—presented an alternative to Fisher’s version of Quantity Theory.

They have attempted to establish that the Quantity Theory of Money is a theory of demand for money (or liquidity preference). The Cambridge version of the Quantity Theory of Money is now presented.

Formally, the Cambridge equation is identical with the income version of Fisher’s equation: M = kPY, where k = 1/V in the Fisher’s equation.

Here 1/V = M/PT measures the amount of money required per unit of transactions and its inverse V measures the rate of turnover or each unit of money per period.

So if k and Y remain constant, P is directly proportional to the initial quantity of money (M).

Criticisms:

1. The Chain of Causation:

Critics argued that all the factors in the equation of exchange are variables and statistical studies have shown that they are interrelated. Moreover, the line of causation is not always from M (money supply) to P (the price level). It may be from V to P. A change in the rate of spending, all the other factors remaining the same, will result in a change in prices just as surely as would a change in the Quantity Theory of money, other things remaining the same.

Or a change in T, other things remaining the same, will cause a change in prices. So it is difficult to accept the theory that changes in the quantity of money are always the causes in the price level. Studies have shown that the price level cannot be easily and quickly controlled by changing the amount of money and credit available for the purchase of goods and services.

It may also be said that, under certain circumstances, an increase in the quantity of money will not produce any change in the price level. Keynes has pointed out that the Quantity Theory is inapplicable to a country which has unemployed resources (capital and labour not in use).

In such a country, creation of more money will lead to more employment and higher production (larger supply of goods) and no change in the price level. Prices will change in proportion to money supply only when there is no scope for increasing production, i.e., when there are no unemployed resources in the economy.

2. There are Inactive Balances:

Under Fisher’s formula, the price level depends upon the total quantity of money. But it is only a part of the total quantity of money which influences prices. There always exist inactive balances (hoards) which exert no pressure at all on the prices of goods and services. This is clearly seen during depressions.

3. Simultaneous Changes:

The Quantity liquation cannot be used for analysing the effects, of changes in M, or T, on the price level except on the ceteris paribus assumption, “other things remaining constant.” But in the case of monetary variables such an assumption cannot be made. When M changes, T and V both change. When T changes, M, and V change. The net effect on the price level of a change in any of the variables of the quantity equation depends on how the other variables are simultaneously changed.

4. The Process of Change:

Theory does not show the process through which changes in the amount of money affect the price level. Keynes put great emphasis on this point.

He observed that:

“The fundamental problem of monetary theory is not merely to establish identities or statistical relation but to treat the problem dynamically, analysing the different elements involved in such a manner as to exhibit the causal processes by which the price-level is determined and the method of transition from one equilibrium to another.”

5. The Assumption of Full Employment:

So increase in the quantity of money does not always increase prices. If there are unemployed resources, increase of money increases employment and not prices. As Keynes points out, the Quantity Theory is based on the assumption of Full Employment.

6. The Value of Money Determines the Quantity of Money:

According to Quantity Theory, an increase in the supply of goods or it will cause a fall in the price level P. Monetary and banking practices, increases in the supply of goods always leads to an increase in the supply of money (through creation of credit and otherwise). M therefore, depends on T; they are not independent variables. If this view is correct, the value of money is not determined by its quantity; on the contrary it is the value of money which determines its quantity.

7. Non-Monetary Factors:

Prices may change and the value of money vary for reasons entirely unconnected with the quantity of money.

Some examples are given below:

(i) Changes in the level of efficiency wages may change costs of production and affect prices.

(ii) If increase of output occurs under conditions of diminishing returns, marginal costs will rise and prices will rise. Similarly, prices will fall if production increases under conditions of increasing returns.

(iii) Increase and decrease of monopoly power will, respectively, increase and decrease prices.

(iv) Prices are affected by variations in effective demand or expenditure. Consumption expenditure and investment expenditure both vary—as also the proportion between them.

8. Misleading Emphasis:

Finally, according to Crowther the Quantity Theory puts a misleading emphasis on the importance of the quantity of money as the cause of price changes and pays too much attention on the level of prices. In the short rim these principles of the Quantity Theory are not in accord with facts. In actual life the price level and volume of production move up and down in a cyclical pattern.

The Quantity Theory draws pointed attention to one important factor which causes price change, viz., the quantity of money. It is admitted that the quantity formula “hides many links in the chain of causation”, but it is undisputed that the formula gives us a rough and ready method of determining the effects of changes in the quantity of money and certain other factors influencing the price level.

From the above discussion it is clear that the Quantity Theory is inadequate and defective. It has, however, certain merits. Generally, we find that when money supply increases, the price level rises. For example, during 1939-45 in India there was a large increase in the volume of notes and bank advances and the price level rose very fast. Hence, there is some relationship between the quantity of money and the value of money. The Quantity Theory states the relationship not with absolute correctness but only approximately.

Dr. Milton Friedman (the 1976 Nobel Prize winner) believes that the quantity theory of money is true in its simple or cured form, i.e., price (P) varies with quantity of money (M). He believes that there is a proportionality between the quantity of money and the general price level in an economy.